Brazil in the race for the future

Posted on 03. Dec, 2010 by Juliana Russar in Brazil

I’ve just arrived in Cancun to track the Brazilian delegation at CoP-16. I published this overview in Portuguese a little while ago and wanted to share it in English to give a little context about how the Brazilian government is dealing with climate change outside the UN negotiations.

Para ler esse post em português, clique aqui

“Do not be frightened of new ideas, be frightened by old ones.” (John Cage)

In October, Brazil elected its first woman president, Dilma Rousseff, candidate and successor of President Lula, who takes office in January 2011. What can we say about the relationship between Dilma and climate change?

Well, it is no secret that she has always clashed with the demands of the Ministry of Environment and that she was against Brazil taking voluntary reduction goals for CoP-15. And, as I always like to remember, the then head of the Brazilian delegation in Copenhagen said that the environment is an obstacle to sustainable development. Despite her economic views, Dilma talked about these reduction goals in the final presidential debate, when finally the candidates spoke briefly about climate change.

In her first speech as president-elect, Dilma did not even mention the issue, showing that climate change remains marginal and, unfortunately, that the new president has not updated her speech to include the challenges of the 21st century. The priorities remain the same: poverty alleviation, health, education, employment, habitation. Certainly, the topics are essential for our development, but they have a relationship of interdependence, and if the impacts of climate change continue to be ignored, it can affect all the achievements of this agenda. As noted in a previous post, the fact is that there has been some progress, but there is still a lack of political will and maturity on the part of the government to deal with the issue, noting that very few countries in the world are dealing with climate change seriously.

We have no way of knowing how Dilma will deal with the issue, but we know she cannot ignore it or turn back, since we have several instruments to monitor and pressure the government, such as the bill on National Policy on Climate Change.

At the annual meeting of the Brazilian Forum on Climate Change with his presence, which usually happens just before the CoPs, President Lula, always skillful in his speeches, said:

Combating global warming is indeed compatible with sustainable economic growth and poverty alleviation and inequality.

However, at the same time, he talked about the oil from pre-salt layer outside the context of climate change, leaving behind its inclusion in the Sector Plans on Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change:

And we do because we do not want that Petrobras is an exporter of crude oil, with the pre-salt. We want it to export petroleum products and for this it has to be international standard, that nobody can complain about, of the best quality.

On 31/10, Dilma said in her speech:

We will treat the resources from our wealth always thinking in the long term. So I will work in Congress to approve the Social Fund of Pre-Salt. Through it, we want to accomplish many of our social goals.

We will refuse ephemeral expenses leaving for future generations just debts and despair.

The Social Fund is a mechanism of long-term savings to support current and future generations. It is the most important product of the new model we have proposed for the operation of the pre-salt, which reserves to the nation and the people the most important portion of these resources.

…

The modern view of economic development is one that values the worker and his family, the citizen and his community, providing access to education and quality health care. It is one that coexists with the environment without damaging it and without creating liabilities greater than the gains of development itself.

That is, as I said, the matter remains marginal, it is only discussed in thematic forums and superficially. And, apparently, the resources from pre-salt became the panacea for all problems of the country and, by the spoken president-elect, the environmental liabilities created by its operation will be justified by the development achievements.

The inclusion of Brazil in a scenario of low carbon growth and implementation of policies for adapting to climate change are not superfluous, but a necessity. This year we had over 40 consecutive days of rain in Sao Paulo during the summer and extremely polluted and dry weather in winter. Let us also remember the rain that affected the Northeast and Rio de Janeiro, frosts in the South out of season. The trend is that extreme events such as these become increasingly frequent and intense, not only causing loss of life, but also economic losses.

In another part of his speech, Lula spoke about the growing emissions from other sectors of the economy besides the land use change and agriculture (which together represent 80% of Brazilian emissions of greenhouse gases), but did not elaborate on what Brazil is doing or will do to slow emissions growth in these sectors:

We have a problem, by the time we will able to control deforestation and the economy grows, we’re changing the emission from deforestation to industrial emissions. And that’s when we need to start doing things before it’s time to do, so we grow together, and together we grow industrially, we develop, but we can also give lessons to the world that we know do things better than they did.

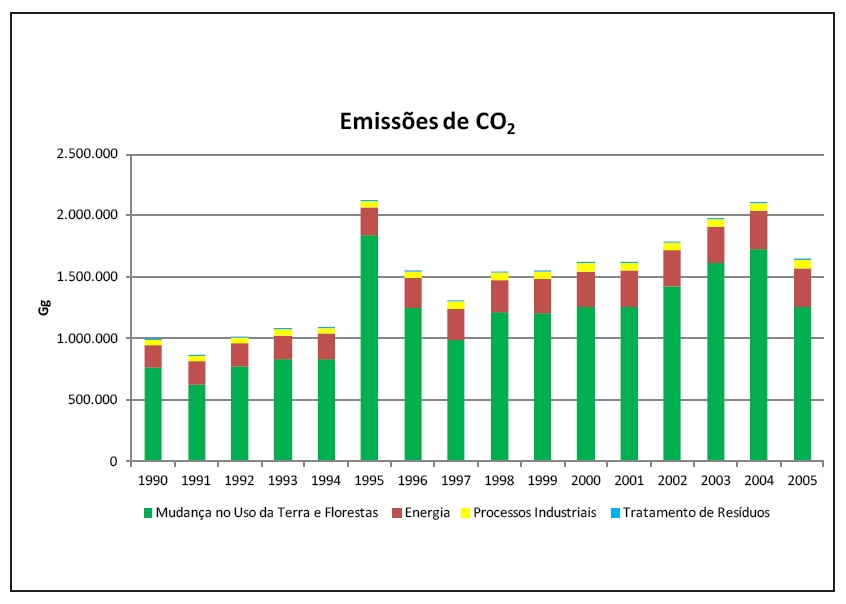

The chart below shows the growth of CO2 emissions from energy and industrial processes. It is known that the emissions related to land use change have dropped dramatically since 2005 due to a number of factors, such as the economic crisis and implementation of more effective policies on command and control and the obligation of environmental licensing requirement for agriculture credit. But would the government be willing to clash with the conservative wing of the energy and industry?

Two studies were published this year that should be on the bedside table of all decision makers in the country.

The first is the report Economics of Climate Change in Brazil: costs and opportunities, inspired by the Stern report and it is the initiative of several research institutions in the country coordinated by FEA/USP and COPPE/UFRJ. In short, according to the report:

• Brazil is likely to lose between U.S.$ 719 billion and $ 3.6 trillion by 2050 if nothing is done to reverse the impacts of climate change, compromising an entire year of growth;

• The poorest regions of the country (North and Northeast) are the most vulnerable, and the cost of inaction today will deepen the regional and income inequalities;

• The generation of hydroelectric power would be compromised, especially in the North and Northeast, reducing 31.5% to 29.3% of firm energy;

• The estimate of material values at risk along the Brazilian coast, considering the worst scenario of rising sea levels and extreme weather events, is R$ 136 billion to $ 207.5 billion;

• Agriculture will be affected and, with the exception of sugar cane, all cultures would suffer reduction of areas with low risk of production, particularly soybeans (-34% to -30%), maize (-15%) and coffee (-17% to -18%).

The study recommends:

- Investment of around R$1 billion per year in research on genetic improvement in crops.

- Installation of extra capacity to generate energy, preferably with natural gas generation, sugarcane bagasse and wind power, a capital cost of U.S. $ 51 billion to 48 billion.

- Implementation of coastal management actions and other public policies that would amount to R$ 3.72 billion by 2050, or about $ 93 million per year.

- Establishment of an average price of carbon in the Amazon region of US$ 3 per ton, or US$ 450 per hectare, which would discourage between 70% to 80% of livestock in the region. The average price of US$ 50 per tonne of carbon could reduce deforestation by 95%.

- Substitution of fossil fuel emissions could avoid 92 million to 203 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent domestic emissions in 2035. Ethanol exports would add 187 million to 362 million tons to emissions avoided on a global scale.

- The taxation of carbon between US$ 30 and US$ 50 per ton of carbon would reduce national emissions between 1.16% and 1.87% and would result in a decline in GDP from 0.13% to 0.08%.

- Compared with the National Energy Plan 2030, the estimated potential of emission reduction would be 1.8 billion tons of CO2 accumulated in the period 2010-2030. With a discount rate of 8% per annum, the estimated cost would be negative, i.e. there would be a gain or benefit, of US$ 34 billion in 2030, equivalent to U.S. $ 13 per tonne of CO2.

The Low Carbon Study for Brazil was prepared by the World Bank and also in short says:

• It will require on average R$ 44 billion (US$20 billion) more per year in investments to implement a low-carbon scenario in Brazil until 2030, keeping the development goals set by the Brazilian government for that period, without any negative impact on growth or job creation. So it would be possible to reduce emissions by 37% of greenhouse gas gross over the period 2010-2030;

• The implementation of the options of Low Carbon Scenario from 2010 to 2030 would require US$ 725 billion (in real terms), more than twice the amount of funding required compared with US$ 336 billion of the reference scenario, which considers policies already implemented and the Government’s plans.

• The distribution of this amount is U.S. $ 334 billion for energy, U.S. $ 157 billion for land use, land-use change and forestry; $ 141 billion for transportation and $ 84 billion for waste management.

• According to the reference scenario, it takes about 17 million hectares of additional land to accommodate the expansion of all activities involving the use of land during the period 2006 to 2030.

• In a scenario of Low Carbon emissions from deforestation would be avoided which would correspond to about 6.2 GtCO2e (billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent) in the period 2010-2030;

• In the regional transport, the study showed a potential to reduce emissions by about 9% in 2030, through change of modal for both passenger and cargo.

• If implemented low carbon options, you can remove 213 MtCO2e (million tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent) from the atmosphere in 2030.

• In the energy sector, the adoption of low carbon options make it possible to reduce 297 MtCO2e in 2010, compared with a reference scenario for the same period 458MtCO2e

• In the area of waste management, adoption of low carbon options allow to reduce 18MtCO2e in 2030, compared with the Reference Scenario of 99MtCO2e.

Based on the findings and notes of these studies, we conclude that including climate change to the development agenda can only bring benefits to the country and enable Brazil to occupy its space with legitimacy as a leader in the international arena, being in the position to demand actions from the other major emitters greenhouse gases.

Negotiator Tracker - Juliana Russar

Juliana mora em São Paulo e sempre foi apaixonada por pol�tica internacional e desenvolvimento. Não por acaso, ela se formou em Relações Internacionais e fez especialização em Meio Ambiente. Desde 2007, tem acompanhado as negociações internacionais sobre mudanças climáticas ... leia mais»

Read more of Juliana's posts here.

Follow Juliana on twitter @jrussar